gRPC on HTTP/2 Engineering a Robust, High-performance Protocol

In a previous article, we explored how HTTP/2 dramatically increases network efficiency and enables real-time communication by providing a framework for long-lived connections. In this article, we’ll look at how gRPC builds on HTTP/2’s long-lived connections to create a performant, robust platform for inter-service communication. We will explore the relationship between gRPC and HTTP/2, how gRPC manages HTTP/2 connections, and how gRPC uses HTTP/2 to keep connections alive, healthy, and utilized.

gRPC Semantics

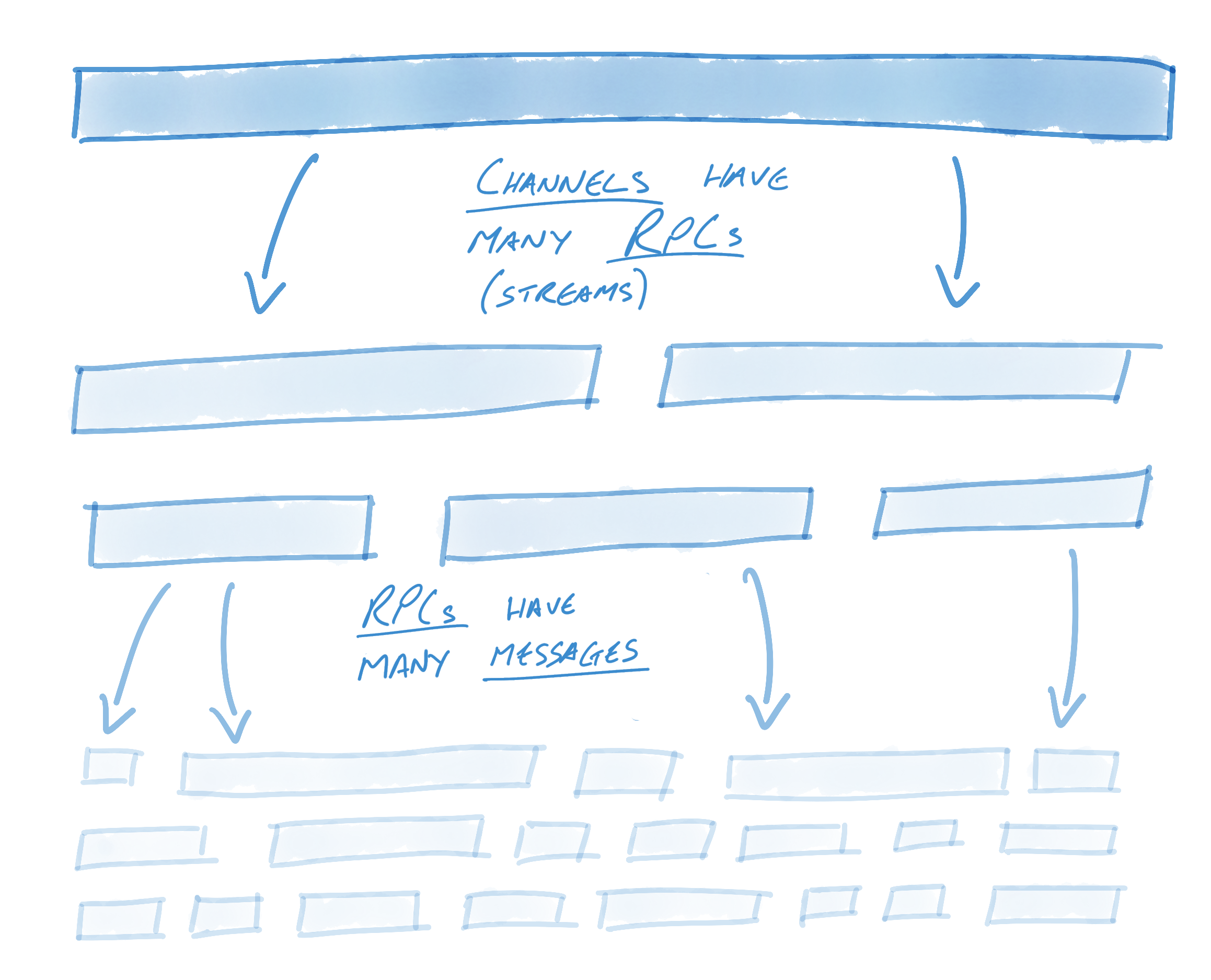

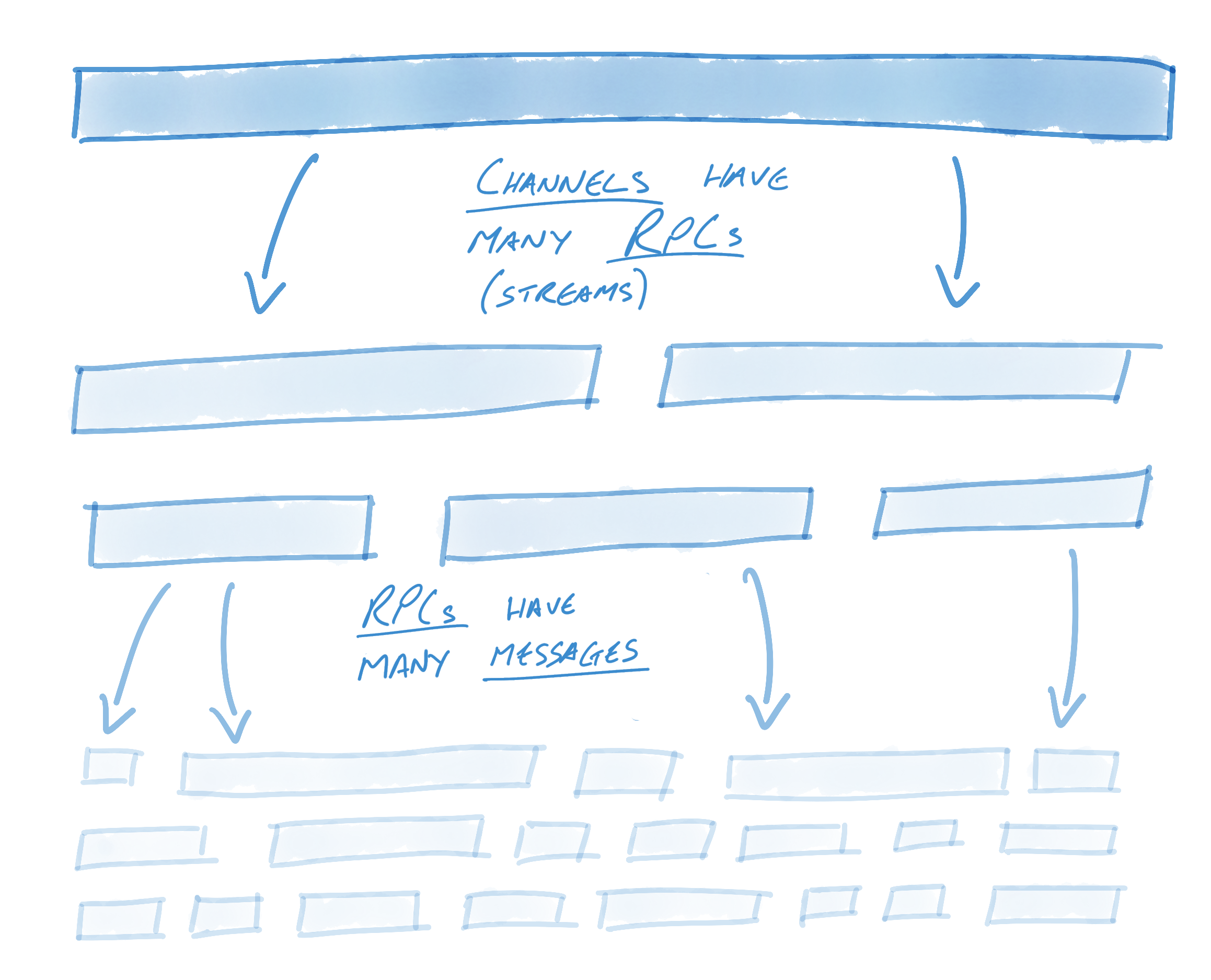

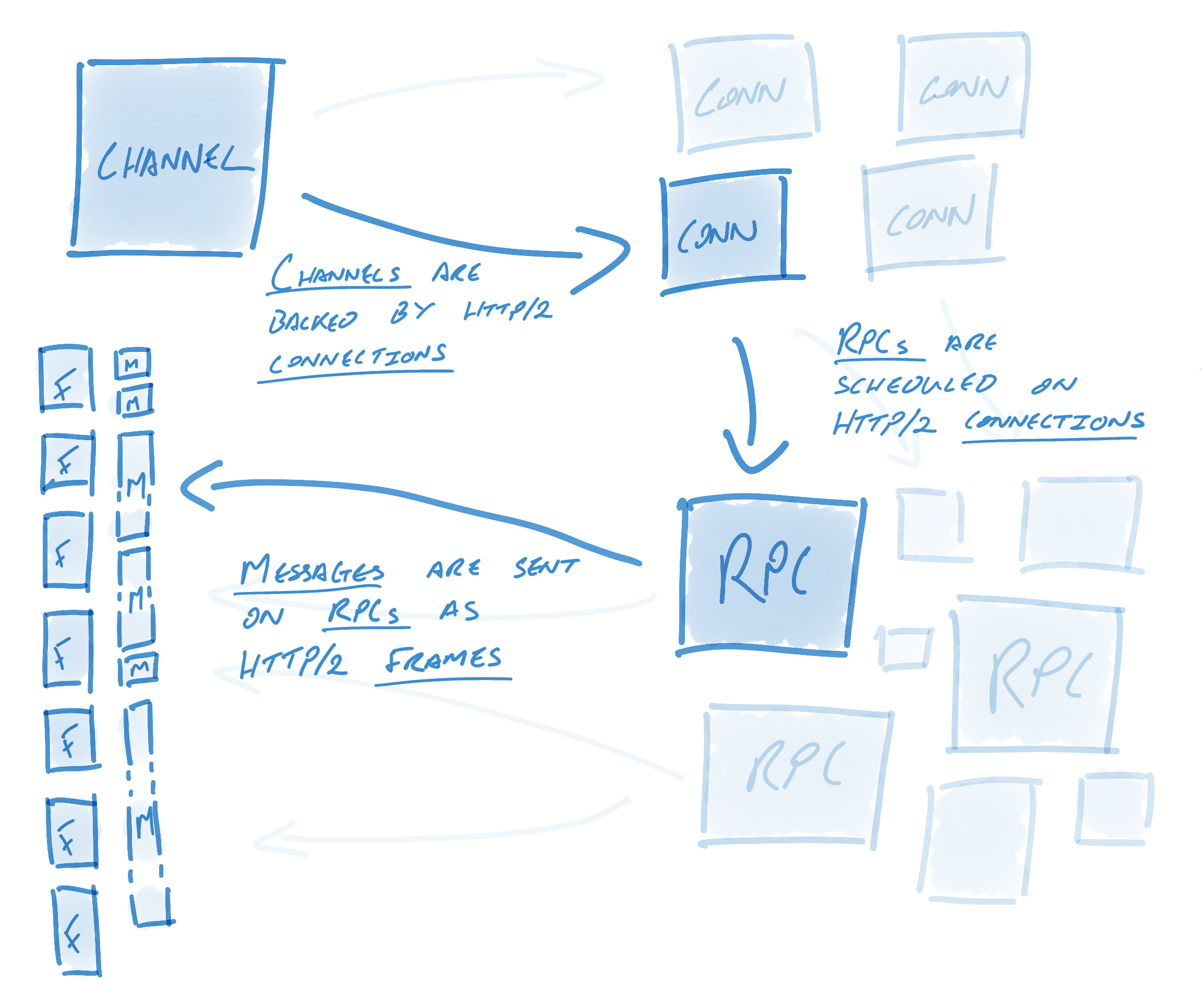

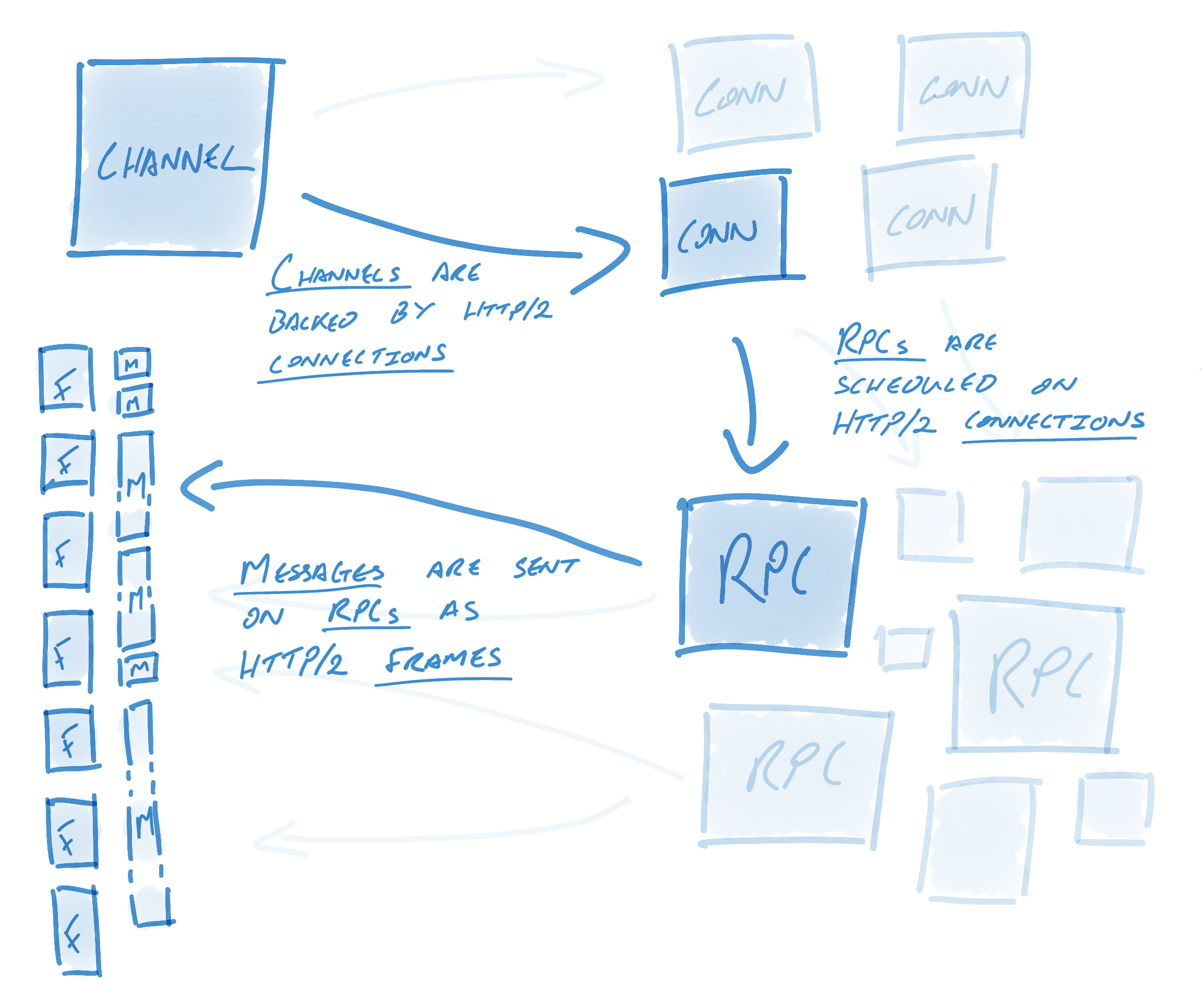

To begin, let’s dive into how gRPC concepts relate to HTTP/2 concepts. gRPC introduces three new concepts: channels1, remote procedure calls (RPCs), and messages. The relationship between the three is simple: each channel may have many RPCs while each RPC may have many messages.

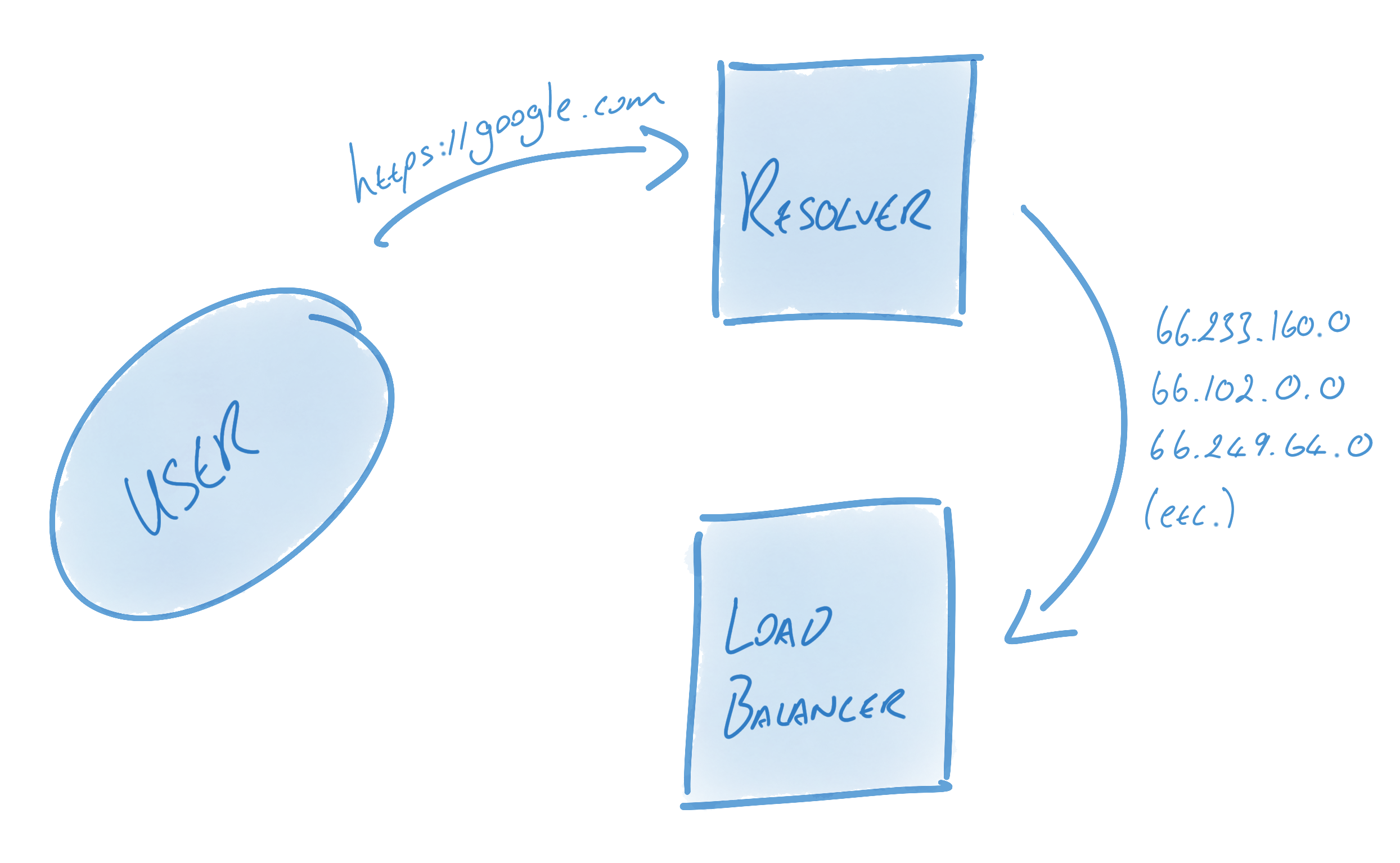

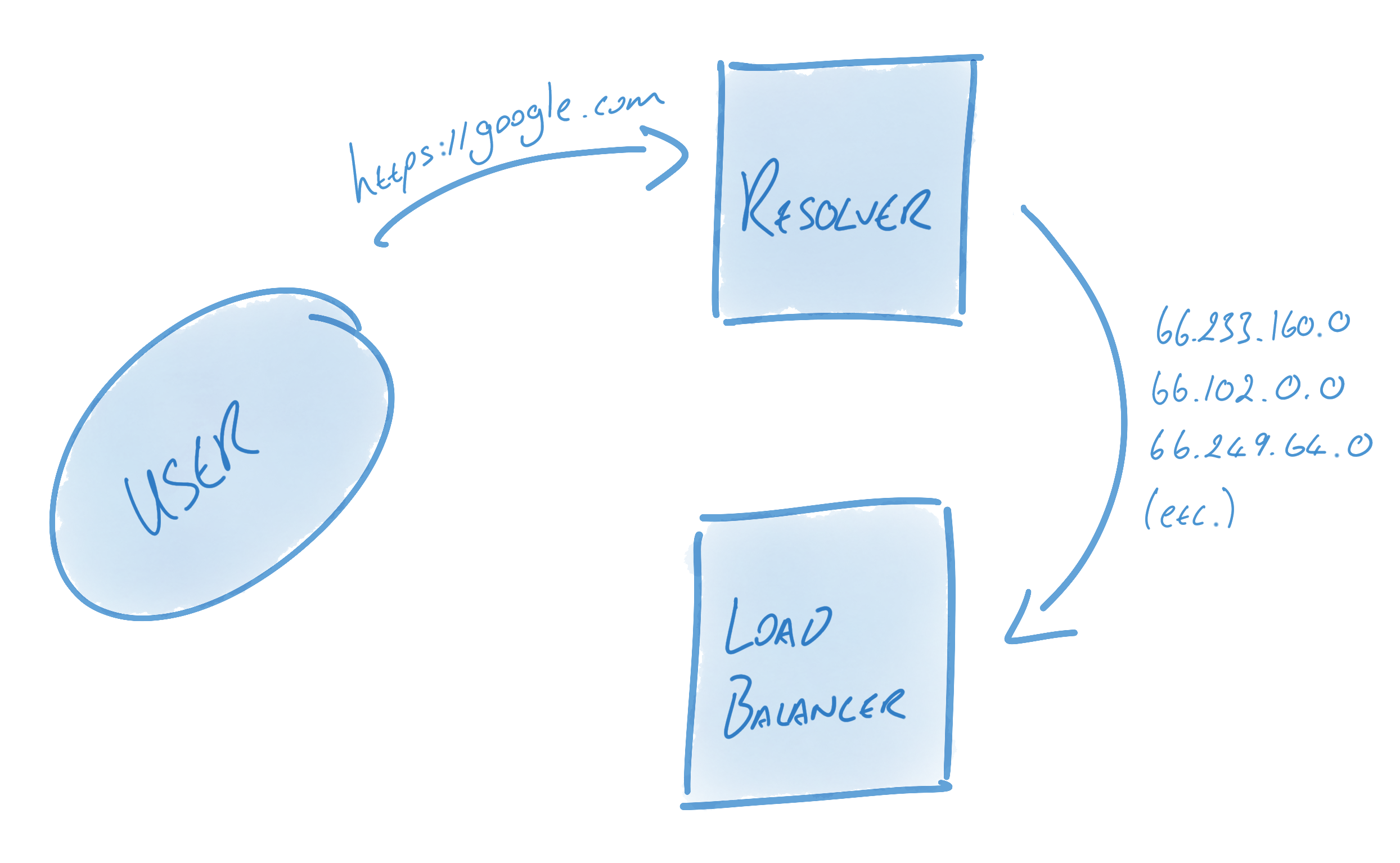

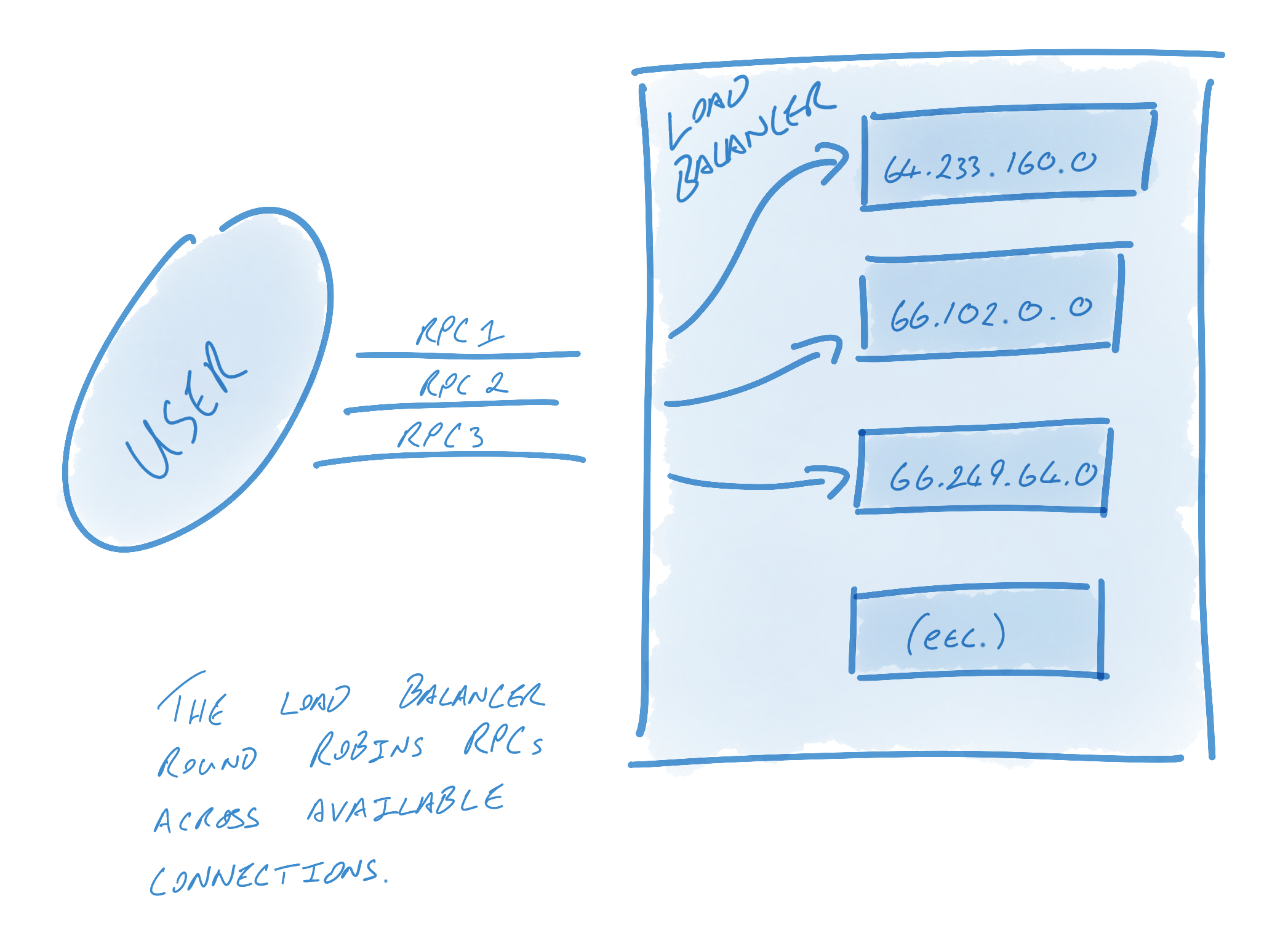

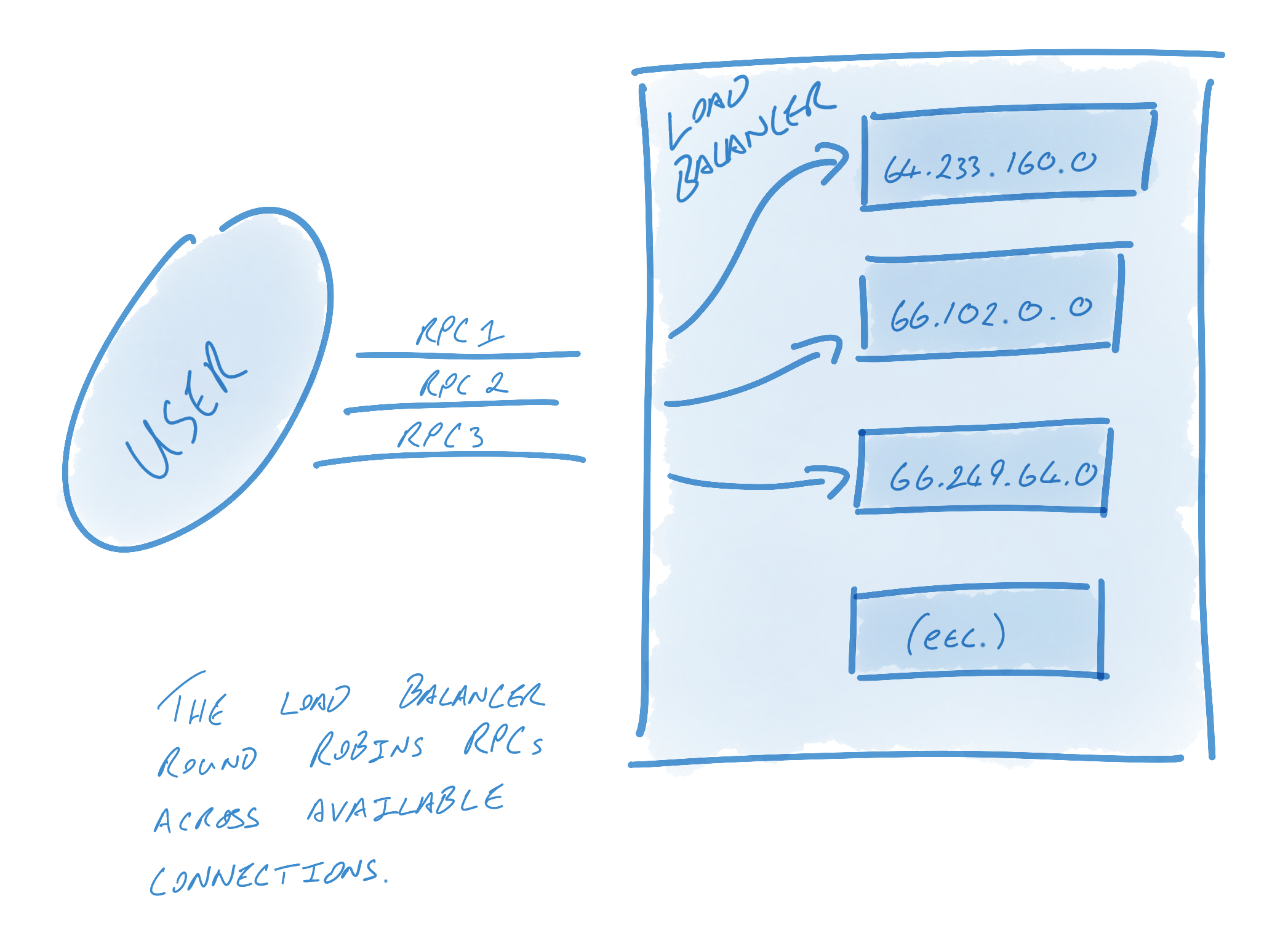

Let’s take a look at how gRPC semantics relate to HTTP/2: Channels are a key concept in gRPC. Streams in HTTP/2 enable multiple concurrent conversations on a single connection; channels extend this concept by enabling multiple streams over multiple concurrent connections. On the surface, channels provide an easy interface for users to send messages into; underneath the hood, though, an incredible amount of engineering goes into keeping these connections alive, healthy, and utilized. Channels represent virtual connections to an endpoint, which in reality may be backed by many HTTP/2 connections. RPCs are associated with a connection (this association is described further on). RPCs are in practice plain HTTP/2 streams. Messages are associated with RPCs and get sent as HTTP/2 data frames. To be more specific, messages are layered on top of data frames. A data frame may have many gRPC messages, or if a gRPC message is quite large2 it might span multiple data frames. In order to keep connections alive, healthy, and utilized, gRPC utilizes a number of components, foremost among them name resolvers and load balancers. The resolver turns names into addresses and then hands these addresses to the load balancer. The load balancer is in charge of creating connections from these addresses and load balancing RPCs between connections. A DNS resolver, for example, might resolve some host name to 13 IP addresses, and then a RoundRobin balancer might create 13 connections - one to each address - and round robin RPCs across each connection. A simpler balancer might simply create a connection to the first address. Alternatively, a user who wants multiple connections but knows that the host name will only resolve to one address might have their balancer create connections against each address 10 times to ensure that multiple connections are used. Resolvers and load balancers solve small but crucial problems in a gRPC system. This design is intentional: reducing the problem space to a few small, discrete problems helps users build custom components. These components can be used to fine-tune gRPC to fit each system’s individual needs. Once configured, gRPC will keep the pool of connections - as defined by the resolver and balancer - healthy, alive, and utilized. When a connection fails, the load balancer will begin to reconnect using the last known list of addresses3. Meanwhile, the resolver will begin attempting to re-resolve the list of host names. This is useful in a number of scenarios. If the proxy is no longer reachable, for example, we’d want the resolver to update the list of addresses to not include that proxy’s address. To take another example: DNS entries might change over time, and so the list of addresses might need to be periodically updated. In this manner and others, gRPC is designed for long-term resiliency. Once resolution is finished, the load balancer is informed of the new addresses. If addresses have changed, the load balancer may spin down connections to addresses not present in the new list or create connections to addresses that weren’t previously there. The effectiveness of gRPC’s connection management hinges upon its ability to identify failed connections. There are generally two types of connection failures: clean failures, in which the failure is communicated, and the less-clean failure, in which the failure is not communicated. Let’s consider a clean, easy-to-observe failure. Clean failures can occur when an endpoint intentionally kills the connection. For example, the endpoint may have gracefully shut down, or a timer may have been exceeded, prompting the endpoint to close the connection. When connections close cleanly, TCP semantics suffice: closing a connection causes the FIN handshake to occur. This ends the HTTP/2 connection, which ends the gRPC connection. gRPC will immediately begin reconnecting (as described above). This is quite clean and requires no additional HTTP/2 or gRPC semantics. The less clean version is where the endpoint dies or hangs without informing the client. In this case, TCP might undergo retry for as long as 10 minutes before the connection is considered failed. Of course, failing to recognize that the connection is dead for 10 minutes is unacceptable. gRPC solves this problem using HTTP/2 semantics: when configured using KeepAlive, gRPC will periodically send HTTP/2 PING frames. These frames bypass flow control and are used to establish whether the connection is alive. If a PING response does not return within a timely fashion, gRPC will consider the connection failed, close the connection, and begin reconnecting (as described above). In this way, gRPC keeps a pool of connections healthy and uses HTTP/2 to ascertain the health of connections periodically. All of this behavior is opaque to the user, and message redirecting happens automatically and on the fly. Users simply send messages on a seemingly always-healthy pool of connections. As mentioned above, KeepAlive provides a valuable benefit: periodically checking the health of the connection by sending an HTTP/2 PING to determine whether the connection is still alive. However, it has another equally useful benefit: signaling liveness to proxies. Consider a client sending data to a server through a proxy. The client and server may be happy to keep a connection alive indefinitely, sending data as necessary. Proxies, on the other hand, are often quite resource constrained and may kill idle connections to save resources. Google Cloud Platform (GCP) load balancers disconnect apparently-idle connections after 10 minutes, and Amazon Web Services Elastic Load Balancers (AWS ELBs) disconnect them after 60 seconds. With gRPC periodically sending HTTP/2 PING frames on connections, the perception of a non-idle connection is created. Endpoints using the aforementioned idle kill rule would pass over killing these connections. HTTP/2 provides a foundation for long-lived, real-time communication streams. gRPC builds on top of this foundation with connection pooling, health semantics, efficient use of data frames and multiplexing, and KeepAlive. Developers choosing protocols must choose those that meet today’s demands as well as tomorrow’s. They are well served by choosing gRPC, whether it be for resiliency, performance, long-lived or short-lived communication, customizability, or simply knowing that their protocol will scale to extraordinarily massive traffic while remaining efficient all the way. To get going with gRPC and HTTP/2 right away, check out gRPC’s Getting Started guides.

Resolvers and Load Balancers

Connection Management

Identifying Failed Connections

Keeping Connections Alive

A Robust, High Performance Protocol

Footnotes